UNLIKELY FRIENDS

A young West Indian boy and a thick set man dressed in shabby clothes and with a scarred face, weave their way through the crowded, grimy streets of 18th century London. They are oblivious to the strangers who watch in bemusement as they determinedly navigate the alleyways that will lead them home.

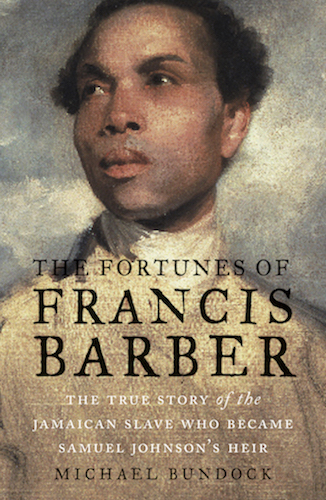

The man, who is famous for his formidable intelligence and the brilliance of his writing, is Doctor Samuel Johnson; poet, essayist and compiler of the first English language dictionary. His companion is Francis Barber, a Jamaican born slave who was given to Johnson after he was brought to England by his owner. Barber became such an important figure in the doctor’s life that when Johnson died in 1784 he left him the bulk of his estate – much to the resentment of his friends! So why has history relegated Barber to a footnote in the Doctor’s story? In fairness, little is known about him which means that anyone attempting to write his biography is likely to be hamstrung by a shortage of information. Yet, that hasn’t deterred Doctor Johnson expert Michael Bundock from producing a splendidly researched and highly readable book that does a valiant job of wresting its subject from the shadows.

“Poor Blacky” and “the doctor’s Negro servant” were among the epithets foisted on Barber by Johnson’s associates, yet he was luckier than most slaves who under the law were defined as chattels. Through the diaries of Thomas Thistlewood, the English owner of a Jamaican sugar plantation, Bundock uncovers the horrific world of brutality that Barber was fortunate enough to escape:

“Flogged Lincoln, for disobedience in not fishing for me as I ordered him. Put him in the bilboes (iron fetters), and then flogged Dick for not bringing him to me…Also flogged Strap for going with grass to the Bay to sell without coming for a ticket…and other impudent tricks.”

Flogging or chaining was a normal way of keeping slaves under control although it wasn’t the only method plantation owners relied on. Sexual abuse was typical (Thistlewood’s diary reveals that during his 37 years in Jamaica he had sex 3,852 times with 138 women), coupled with extreme punishments designed to humiliate and degrade. The treatment meted out to Derby, another of Thistlewood’s slaves, was particularly disgusting:

“Derby…catched by Port Royal eating canes. Had him well flogged and pickled, then made Hector shit in his mouth.”

Although Barber avoided those indignities when he arrived in England as a seven-year-old in 1750, he couldn’t avoid the general prejudice that ran through society. Yet, in Samuel Johnson he found a man of generosity and paternal feeling. When Barber joined the navy a worried Johnson pulled out all the stops to get him discharged, even though the youngster hadn’t been coerced into service but had signed up of his own accord. It was the doctor who paid for him to go to grammar school and who supported Barber’s marriage in 1773 to Elizabeth Ball, a white English woman. In over thirty years of living together the Johnson/Barber relationship eased from master/servant towards something that could almost be described as familial. Why?

Maybe what strengthened the obvious affection they had for each other was their position as outsiders. Barber was black and in a mixed-race relationship while Johnson, a highly vocal opponent of slavery, had a distinctive physical appearance that made him stand out for all the wrong reasons. The writer Fanny Burney described him as “ugly”, while others noted “his loud and imperious voice” and how his body would involuntarily spasm when he moved, a possible sign of Tourette’s syndrome. Johnson abhorred social fads and ran a household that was chaotically eccentric:

“Williams hates everybody. Levet hates Demouslins and does not love Williams. Desmoulins hates them both. Poll loves none of them”.

The Trials of Francis Barber is a crisp, eloquently written book that makes an excellent job of bringing definition to a man whose story has been largely neglected. Bundock is sympathetic to his subject, endowing him with dignity whilst emphasising his devotion to a larger than life personality who probably wasn’t easy to live with.

Whatever his faults Samuel Johnson was still a man ahead of his time. In leaving most of his wealth to Barber, he was underscoring a basic principle: the quality of a man is what matters in life rather than the colour of his skin.

Reviewed by Juliette Foster

© Archant Community Media Limited used under limited licence