BEWARE THE MARKETS

How should history remember Alan Greenspan? As the US Federal Reserve Chairman who made America rich? Or as a monetarist villain whose policies sowed the ground for the 2007/2008 financial crash? The fact the question even arises is a measure of how far his star has fallen. Once lauded as an economics maestro, Greenspan’s eerily brilliant grasp of numbers and financial minutiae kept him at the Fed for 18 years making him one of its longest serving chairman. Not bad for a man who once called the central bank “one of the historic disasters in American history”.

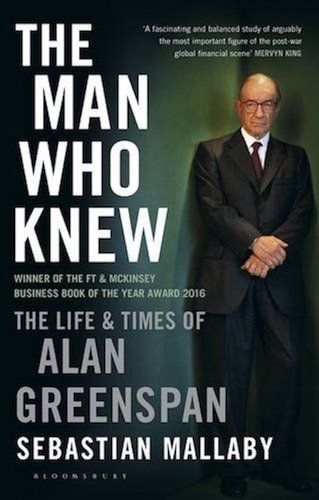

So how did Greenspan go from hero to zero, and why did he forge a system that would prove to be dangerously unstable? The Man Who Knew is Sebastian Malleby’s masterly analysis of the shy son of a Jewish single mother who went from a musician in a second-tier jazz band to a brilliant economic forecaster, before reaching his career pinnacle in 1987 when he was appointed to the role that would ultimately define him. His rise from humble beginnings in New York to the dizzying heights of success is a classic American Dream story, albeit with the tragic twist of a narrative turning against its subject.

I first came across Allan Greenspan in the 1990s when I was working in Bloomberg Television’s London bureau. This was the decade when anything with dot com behind its name was ripe for an IPO (Initial Public Offering), no matter how questionable the business plan. That fact was enough to concern financial analysts who feared that overpriced technology stocks in an irrationally exuberant market were inflating an almighty bubble. It needed pricking and it was Greenspan who did the honours. Part of my job was to listen to his briefings for clues on his strategy and it was no easy task. Not only were his speeches long but they were often sprinkled with deliberate ambiguities. Just when we thought we knew where he was going, Greenspan the consummate showman, would shatter our assumptions with some well-aimed curveballs. The deftly beguiling manner in which he played the media was often mirrored in his handling of the Washington political tribe. Pragmatism, intelligence, and guile were his trademarks. Allied to those qualities was the unbending individualism that would bring him to the attention of Ayn Rand, the Russian émigré novelist who Greenspan met through his first wife.

Rand’s fierce advocacy of libertarianism, a philosophy that embraces free markets, the value of selfishness in all things, and the merits of a radically reduced state, appealed to Greenspan’s logic. She also shared his admiration for nineteenth century American industrialists, so called Robber Barons like the steel boss Andrew Carnegie and the railroad magnate James J Hill, who built their empires without the benefit of federal budgets or regulatory encumbrances. Rand’s influence on her protégé was deep and Greenspan never away shied from displaying his libertarian colours. At a 1961 meeting of the National Association of Business Economists, he unleashed a fiery attack on government efforts to rein in monopolies with anti-trust laws:

“The world of anti-trust is reminiscent of Alice’s Wonderland: everything seemingly is, yet apparently isn’t, simultaneously. It is a world in which competition is lauded as the basic axiom and guiding principle, yet “too much” competition is condemned as “cutthroat”. It is a world in which actions designed to limit completion are branded as criminal when taken by businessmen, yet praised as “enlightened” when initiated by the Government.”

It was no coincidence that when Greenspan was sworn in as Gerald Ford’s chairman of the Council of Economic Advisors, Rand was among the invited guests at the White House ceremony. The irony was that his later actions would contradict his mentor’s principles. Like President Reagan he believed in the gold standard yet steered him away from it: despite voicing his opposition to bailouts he switched on the financial taps when countries or weak institutions needed cash: he understood the dangers of moral hazard yet offered his support to the markets through what became known as the “Greenspan put”.

The paradox is fascinating but unsurprising as Greenspan’s ambition was to be in the political centre. Flexibility was crucial and if that meant reining in his libertarian instincts, then so be it. It was a lesson learned in 1968 during his time as a policy advisor to Richard Nixon’s presidential campaign. Greenspan denied he wanted a senior post in a Nixon administration, yet the truth was that his early libertarianism had not been forgotten and in the eyes of the president’s men that made him unreliable. That didn’t mean Nixon wasn’t averse to using him. Mallaby reveals that Greenspan had a hand in getting Fed Chairman Arthur Burns to back off from talking down the economy during the run up to the 1972 election. The president’s dirty tricks squad planted negative stories about Burns in the press and when that didn’t work, Greenspan agreed to have a word with his friend and one-time mentor. Greenspan’s later denial of any involvement looks disingenuous given Burns’ subsequent change of tune. It wasn’t Greenspan’s finest hour and there are other examples of his wheeler dealing that present him in a less than flattering light. Yet those transgressions shouldn’t detract from the positives.

Mallaby highlights Greenspan’s genius for data analysis, which showed itself in 1996 when he solved the mystery of weak productivity against rising corporate profits. This mattered because flat productivity meant inflation was looming which would have forced the Fed to raise interest rates. Greenspan suspected that productivity was rising faster than the aggregate numbers suggested, but he had to prove it. He ordered his researchers to examine the data of 155 categories of firms going back to 1960. In “a prodigious trove of data – even by the standards of the Fed”, Greenspan found the answer he was looking for. Weak service sector productivity was “depressing the economy wide numbers”, yet that didn’t make sense because of the amount of money that law firms, business consultancies, and others were investing in information technology. It could only point to one conclusion: the data was flawed. US productivity was actually growing faster than the official numbers suggested. A week later when the Fed convened and the regional presidents argued the case for a rate rise, Greenspan “like a magician unfurling a silk scarf”, played his ace. The policy hawks backed down and rates were left alone.

By the time George W Bush was sworn in as America’s 43rd President, Greenspan’s reputation had made him untouchable. He was the legend among giants who on his 2006 retirement had the world at his feet, yet it was the housing bubble which had built up during his watch that would be his undoing. Property prices nosedived, sub-prime lenders filed for bankruptcy, while two hedge funds run by the investment bank Bear Stearns collapsed. As the crisis escalated the blame game rolled into touch with Greenspan as the obvious fall guy. Was this justified? He understood the fragility of financial systems and was historically conscious of market bubbles, yet as Mallaby argues:

“The tragedy of Greenspan’s tenure is that he did not pursue his fear of finance far enough: he decided that targeting inflation was seductively easy, whereas targeting asset prices was hard; he did not like to confront the climate of opinion which was willing to grant that central banks had a duty to fight inflation, but not that they should vaporize citizens’ savings by forcing down asset prices.”

That “climate of opinion” is politics and it is politicians as much as Greenspan himself who should also take a share of the blame for what eventually happened. It was Jimmy Carter who removed the last traces of bank interest rate regulation: Bill Clinton who repealed the Depression era Glass Steagal Act, which forbade commercial banks from taking part in investment banking activity. Rules designed to govern bank capital instead deferred to the banks own risk models, or as Malleby puts it “effectively handing the teenagers the keys to the Mercedes.” Powerful forces were driving financial evolution and deregulation was the response. Could anyone have foreseen how it would conspire to bring a market to its knees? Probably not.

Alan Greenspan was the model public servant who understood better than most how markets and the real economy interacted. He wasn’t afraid to punch back when politicians threatened to invade his space and for 18 years he calmly exerted his authority over the Fed, despite the limits to his power. He operated in “cramped terrain, boxed in by a clamorous multitude of turf fighters and string pullers and influence peddlers.” However, that does not excuse his mistakes. He knew that asset prices were rising yet he kept the onus on fighting inflation. Greenspan could have changed tack to focus monetary policy on building a stable future. He was powerful enough in his own right to have at least attempted a move in that direction. The fact that he didn’t is why to some people he will always be a villain.

Reviewed by Juliette Foster

This article first appeared In Dante Magazine