WORKING GIRL

By any measure, Louise Delabigne was an extraordinary woman! Born in a Parisian slum in 1848 to a single parent who was also a prostitute, Louise could have followed the predictable template of her mother’s life, instead she subverted it! Through a combination of ambition, good looks, and shrewd thinking Louise made her name as a highly paid sex worker, or courtesan, who at the time of her death in 1910 had amassed the equivalent of a multi-million-pound fortune. The red hair, blue eyes, and perfectly proportioned nose that had made her a standout beauty as a child, enticed some of France’s most powerful men into her bed including princes, bankers, diplomats and (allegedly) the emperor Napoleon 111. Reinventing herself as the glamorous Comtesse Valtesse de la Bigne, Louise was a high society darling whose elegant wit brought her friends in high places and inspired Emile Zola to write his deliciously scandalous novel, Nana. So, how did she do it?

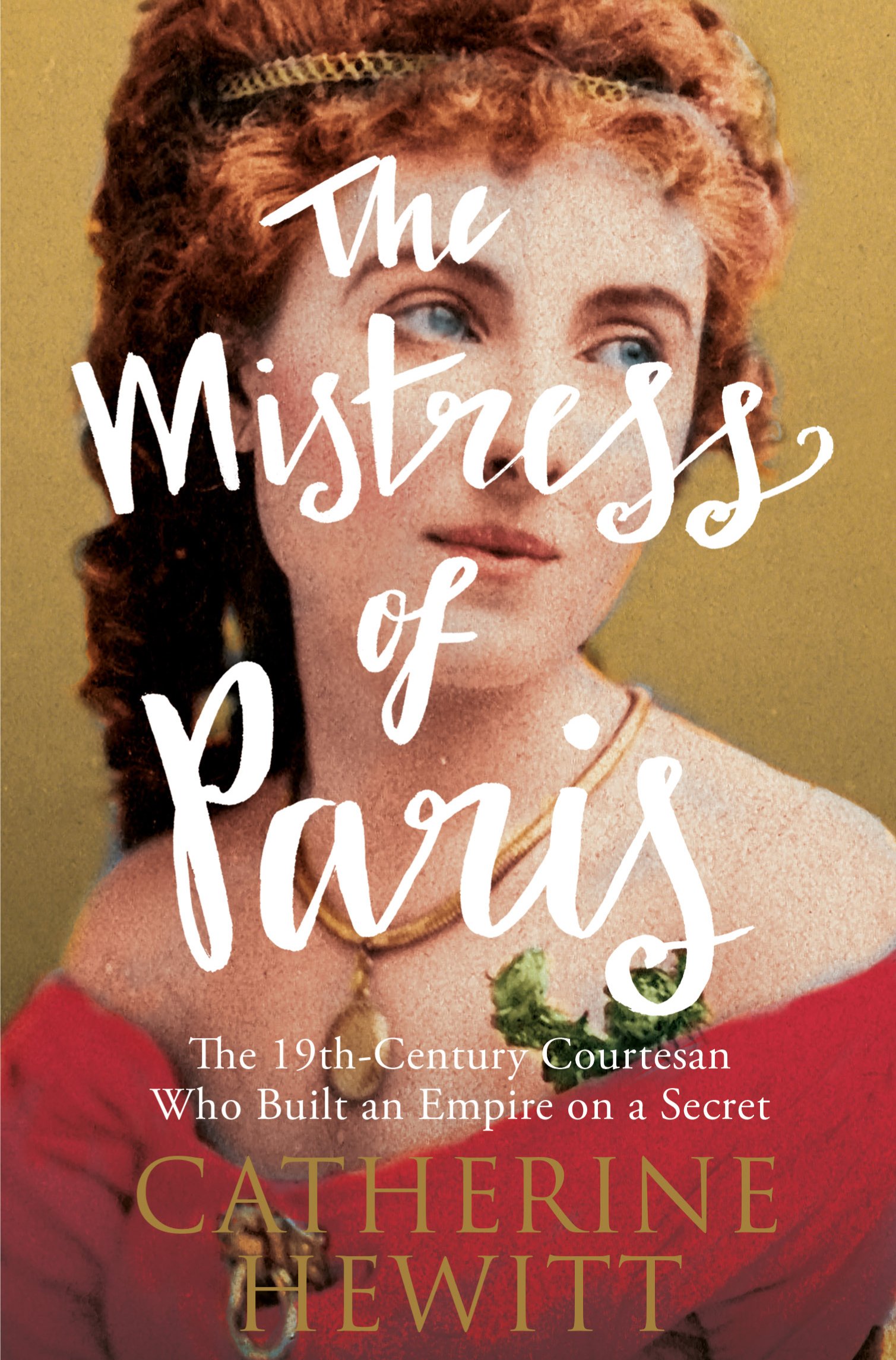

In The Mistress of Paris, author Catherine Hewitt takes the reader on an eventful jaunt through the life of a woman who, behind the charm, was a ruthless strategic thinker! Valtesse’s public image was cultivated to perfection, yet her past could have easily undone her which is why no effort was spared in keeping as much of a distance between herself and the poverty she had escaped. A tiny clique of trustworthy associates were her entourage, including Camille Meldola her formidable house-keeper. They were childhood friends and for Valtesse, who valued loyalty above all else, handing the running of her homes to the woman who had stood by her through thick and thin was the logical thing to do. Unfortunately, Valtesse’s mother was anything but loyal.

Before hitting the big time, Valtesse had given birth to two illegitimate daughters one of whom died young. A monthly allowance was paid to her mother for the care of the surviving child, an arrangement that had worked reasonably well until Madame Delabigne filed for permanent custody. Up until then nobody knew of the child’s existence and Valtesse was painfully aware of the damage to her social position if a court judgement went against her. She needn’t have worried! Thanks to some persuasive arguments from her lawyer, and her dignified presence in court, Valtesse won the day. Although she was criticised in the tabloids for lacking a maternal instinct, influential commentators took her side and that mattered as it was their opinions that carried weight with the public. Valtesse had suspected her mother was grooming her daughter for a life of prostitution and had she not won the case, Madame Delabigne’s plan might very well have succeeded. However, Valtesse was never one to dwell on these things for long having learned early in her career that “a courtesan must never cry.”

Everything about her life (even the lovers divided into categories), was methodically planned. Men from one social group were allowed to take her to the theatre or to dinner, those with deep pockets were invited into her bed, while freebies were reserved for the genuinely broke, or for soldiers (Valtesse couldn’t resist a man in a uniform).

The woman who emerges from the pages of this thoughtful book is resourceful, quick witted, and tough. She had to be! The neighbourhood where she was born was dangerously unsafe and the streets were crawling with predatory men looking for vulnerable women and girls to exploit. Could marriage have been a way out? Perhaps, although the father of Valtesse’s children abandoned her after caving in to family pressure. This might also explain why she made it a point to never fall in love with her clients! There were few genuine career opportunities for working class women like Valtesse and for some prostitution was the only way of putting food on the table. For those who played the game with imagination, the rewards were boundless. Legendary courtesan Cora Pearl was once given a box of candies with a 100 Franc note wrapped around each sweet: Hortense Schneider had a string of aristocratic lovers, while the carriages that transported her around Paris “were the envy of those who promenaded the leafy avenues of the Bois de Boulogne”.

Valtesse may have lived in the nineteenth century but the business model that enriched her doesn’t necessarily look out of place in the twenty first. There are enough examples on the internet of men and women who have turned the economic necessity of sex work into a lifestyle choice paying big dividends. So, what would Valtesse have made of the transformative impact of Facebook, TikTok, and Only Fans on the world’s oldest profession? Who knows, although I half suspect she would have harnessed their potential to make herself the richest courtesan of the millennium!

Reviewed by Juliette Foster