When I told a friend that I was going to Iraq to read my poetry at an Arts Festival in Babylon, they said surely poetry wasn’t relevant there given the violence and bloodshed that had been taking place there over the last few years. I replied surely that was when poetry was most important, given its power to express the inexpressible.

There is an assumption, fostered by the media, that the only thing that people concentrate on in a country torn apart by war/conflict is the conflict itself. But this is very far from the truth.

As well as visiting Babylon, a city not far from Baghdad in Iraq for an arts and cultural festival, a few years ago I spent several months in the Gaza Strip, working in collaboration with the British Council at the university there, at a time when it was being bombed on an almost daily basis.

In both places what I found was not a hornet’s nest of terrorists, but ordinary people trying to have a life, each day filled with all the things that are part of ordinary life. People still went shopping, got married, celebrated birthdays, had babies, and savoured each moment of life while they had it to live. Even when they were living in the midst of terrible devastation, surrounded by rubble and destruction, the urge to continue having an ordinary life remained strong. It underlined the joy of every small triumph over ruination, laughter as well as tears, celebration as well as despair.

I remember one of my students in Gaza had a birthday party. There was a huge cake, dancing, singing and real happiness. Hours later the city was bombed again, and laughter seemed very far away.

Bombs often fell extremely close to the building where I was living. I had been advised that when you were under attack to ‘ignore the bombs and open all the windows’. I thought it odd advice until that night, because the bombs falling so close to my building caused all the windows to shatter, showering the apartment with razor sharp slivers of glass which would have cut me to ribbons had I not locked myself into my bathroom. If the windows had been open, this wouldn’t have happened.

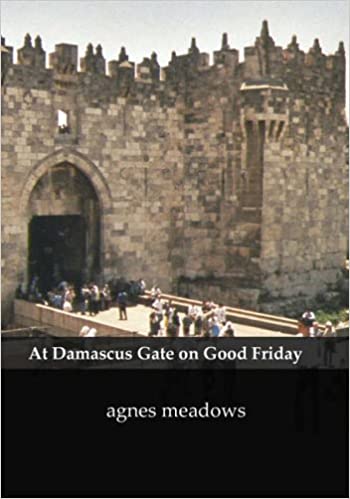

The young people I worked with there were a vibrant, intelligent, lively bunch, who all had dreams of a better, freer life for everyone in Gaza. They loved the poetry readings I gave at the University, and my encouragement of their own writing even though it was somewhat one-dimensional given their narrow experience of life in a war zone. Out of this came my poetry collection ‘At Damascus Gate on Good Friday’.

It was a very different experience in Babylon, because that city wasn’t being bombed, although much of the rest of Iraq was war-torn.

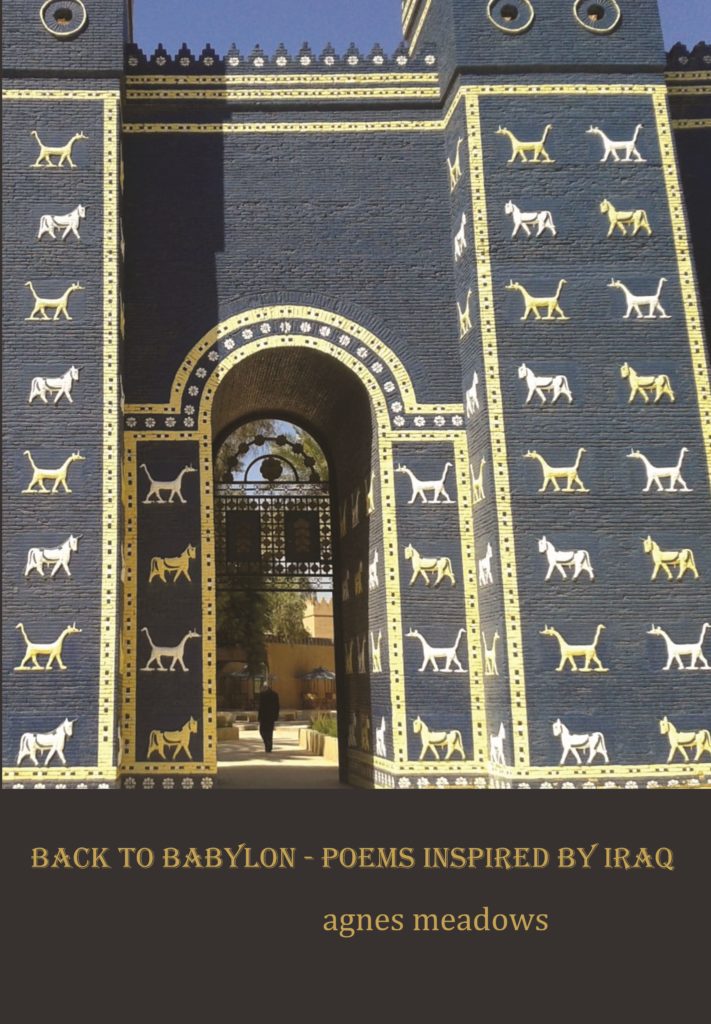

I was invited to read at the 1st Babylon International Festival of Arts & Culture in 2012, by the Festival Director, Dr Ali Al-Salah, an extraordinary man with extraordinary vision. The Festival has been held every year since then…not something that is reported on in the media, and I returned to read again in 2014 and 2016.

Every time I went there, I was overwhelmed by the warmth and hospitality of not only the organisers, but by ordinary (that word again) people who treated all the poets and artists taking part as honoured guests.

The Festival itself was a lively and creative affair, with poets and artists from all over the world, and an audience of locals who clearly loved the art form and showed their appreciation with loud applause. Even the children who attended with their parents sat in rapt attention – so different from what you might see from children in the West.

Time and again, after I had read my poetry, people came up to me with smiles and handshakes, telling me how grateful they were for my attendance, and asking me to tell people back home that they weren’t all extremists or terrorists.

I will always remember the evening when, having supper with some of my fellow writers, we were approached by a young man who had clearly been badly-injured in a roadside ambush, we subsequently discovered. He approached us with trepidation, and asked if we could take a photo of him with us, poets and artists, which he wanted to send to his mother, so she could see that he wasn’t only surrounded by death and destruction. It was a privilege for us to agree to that photograph, and when we saw him again days later, he greeted us in friendship. Out of what I saw and experienced there came my collection ‘Back to Babylon’.

How can you ever forget something like that, not be inspired to write about it, or believe that poetry is irrelevant in a war zone? and

Why not take a look at these poetry collections by Agnes Meadows? Back to Babylon: Poems Inspired by Iraq, Woman, At Damascus Gate on Good Friday and This One is For You